Following last week’s depiction of the Israelites’ apostasy with the Midianites, this week’s Torah portion, Parashat Mattot, contains an exceedingly brutal coda:

Moses spoke to the people, saying, “Avenge the Israelite people on the Midianites; then you shall be gathered to your kin.” Moses spoke to the people, saying, “Let men be picked out from among you for a campaign, and let them fall upon Midian to wreak the Lord’s vengeance on Midian. You shall dispatch on the campaign a thousand from every one of the tribes of Israel.” (Numbers 31:1-4)

Thereupon, twelve thousand Israelites set upon the Midian nation, kill every male and take the women and children captive. The Israelites also kill five Midianite kings, seize the Midianites’ wealth and destroy their towns and encampments by fire.

When the Israelites present their spoil to Moses and the leaders of Israel, Moses is enraged that they did not put the Midianite women to the sword (since they were the ones who “induced the Israelites to trespass against the Lord.” 31:16) Moses then demands that the Israelites kill all the male children as well as every woman “who has known a man carnally.” All virgin Midian women, however, may be spared.

A few examples of how some commentators deal with a text that essentially glorifies genocidal holy war:

First there’s the “abject apologetic approach,” a good example of which may be found in Rabbi Joseph Telushkin’s commentary for CLAL:

The Bible’s troubling ethics of warfare can perhaps be best explained in terms of monotheism’s struggle to survive. After all, it was long a minority movement with a different theology and ethical system than the rest of the world. It developed and expanded because it had one small corner in the world where it grew undisturbed. Had the Hebrews continued to reside amid the pagan, child sacrificing Canaanites, monotheism itself almost certainly would have died.

Then there’s the “use scholarship to deny it ever actually happened, thus avoiding the essential moral problem approach:”

(The) account of Moses’ war against Midian contains a verifiable historical nucleus, even though the quantitative data are not to be taken literally: The amount of spoil is beyond credulity, and one can doubt the the Midianites were annihilated while the Israelites suffered no causalities. …Indeed, if this account of Israel’s victory over the Midianites were not in the Pentateuch, it would have to be invented. (Jacob Milgrom, The JPS Torah Commentary, p. 491)

There’s the technique I call “spiritualizing the text” (i.e., taking these words out of the context of ancient Near Eastern tribal warfare and turning them into metaphors for inner spiritual growth). Rabbi Shefa Gold is among the more eloquent practitioners of this approach:

Moses grew up with two identities: Egyptian prince, and child of Hebrew slaves. When he left Egypt, for all intents and purposes he himself became a Midianite. Moses married Tzippora, a Midianite woman. And his father-in-law Yitro became his teacher. The Midianite tribe became his family. Legend has it that he lived there as a shepherd for 40 years, learning and growing into his calling as prophet…

Whenever we try to reject a part of ourselves, that part becomes our shadow. The shadow is the part of us that is hidden from the light of consciousness. In that moment when blind fury unfolds into hatred against the other, we can be sent from the Lesser Jihad, from the battle in the world, to the Greater Jihad – the battle within. We are jarred into the realization that the external battle is only a dim reflection of the inner battle that has been raging all along. Once exposed, the shadow can be healed.

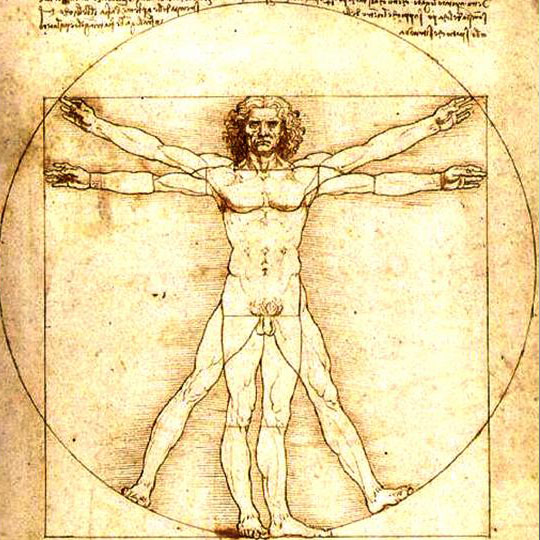

Only when we acknowledge the warring tribes within us, can we begin to make peace, first in ourselves and then in the world. A moment of tragic cruelty, illuminated by the light of humility and wisdom, becomes a hard-earned blessing. In that moment, our identity expands from tribal to universal. In that moment, our tribal identity becomes transparent. The structure of that identity still gives us meaning and comfort, but we can also see right through it and celebrate the many tribes that constitute the human family, all of us interconnected, bound to each other through our shared humanity.

The moment when Moses’ cruelty is unmasked, and we see a man at war with himself, is a moment of blessing. The moment when Moses’ violent turmoil is revealed, we see a man who has rejected a part of himself. This is a moment of blessing. In this moment the spiritual work of healing begins.

And if none of those work for you, there’s the “complete rejection of the text as hopelessly archaic, morally bankrupt, and unredeemable on any level” approach. Check out what the venerable Thomas Paine had to say about Numbers 31:

Among the detestable villains that in any period of the world have disgraced the name of man, it is impossible to find a greater than Moses, if this account be true. Here is an order to butcher the boys, to massacre the mothers, and debauch the daughters. Let any mother put herself in the situation of those mothers; one child murdered, another destined to violation, and herself in the hands of an executioner; let any daughter put herself in the situation of those daughters, destined as a prey to the murderers of a mother and a brother, and what will be their feelings? It is in vain that we attempt to impose upon nature, for nature will have her course, and the religion that tortures all her social ties is a false religion…

People in general do not know what wickedness there is in this pretended word of God. Brought up in habits of superstition, they take it for granted that the Bible is true, and that it is good; they permit themselves not to doubt of it, and they carry the ideas they form of the benevolence of the Almighty to the book which they have been taught to believe was written by his authority. Good heavens! it is quite another thing; it is a book of lies, wickedness, and blasphemy; for what can be greater blasphemy than to ascribe the wickedness of man to the orders of the Almighty? (from “The Age of Reason Pt. II”)

Beyond the various interpretive pedgogies, I’m struck by a few lingering questions from this episode:

– How do we square Moses’ bloodthirsty command, with the fact (as Rabbi Shefa points out) that Moses himself was married to a Midianite – and was in fact mentored by his father in law, the High Priest of Midian? (Exodus 18:13-27)

– What do we make of the way Moses interprets God’s simple and rather general command (“Avenge the Israelite people on the Midianites…”)?

– What do we make of the second part of the command (“…then you shall be gathered to your kin”)? Could the brutality of Moses’ instructions reflect the anger and frustration he experiences before his preordained death? (Not to let God off the hook here for a second…)

– Should we consider it notable that the Torah never mentions whether or not the Israelites actually carried out Moses final command?

Feel free to weigh in.